Lot 3

Southeast Corner of Churton Street and Margaret Lane

Churton's Office

c. 1754

In addition to surveying the town, William Churton held many positions in the local government. He was appointed to be the first public register of Orange County in 1752, served as member from Orange in the colonial legislature from 1754 to 1762, and as town commissioner of Childsburg from its incorporation as a town in 1759 until his death. He was also officially appointed public surveyor of Orange County in 1757 and served as justice of the peace after 1757. Accordingly, he needed a place in town to live and conduct official business and was gifted Lot 3. In the Sauthier map, the lot is depicted with three structures. Historian Mary Clair Engstrom wrote, “the square structure in the NW corner flush with Churton St. and Spring Lane was likely his office. The large rectangular dwelling house set back behind it was probably his own residence … and the very small dwelling house in the NE corner may have belonged to his assistant surveyor Enoch Lewis.”

Detail from the 1768 Sauthier Map showing Lot 3

As land agent, Churton’s job was to sell property and then forward the money collected to Lord Granville in England. Accordingly, he used his office to compose and execute deeds of sale. These documents were known as indentures (“indenture” means contract). The contracts would be written twice on the same piece of paper. They would describe the piece of property being sold and then be signed by both the purchaser(s) and the seller. The paper would be cut in an indented manner with one half given to the purchaser and the other stored with the seller. This process protected against forgery.

A 1755 indenture for a lot in Hillsborough on King Street that was executed by William Churton. The original is on display at the Orange County Historical Museum. Churton would have had many such indentures stored in his office.

In 1759, the colonial legislature granted Churton four additional lots that adjoined this property, "In Consideration of the many Services he hath performed for the Inhabitants of the said Town, and his Labour, Expence, and Pains in laying out the said Town." This gift of lots was reaffirmed in the 1766 legislative bill renaming the town Hillsborough.

Cornwallis' Office

1781

The owners of the property during the time between Churton’s death in 1767 and the next recorded deed in 1785 are unknown. Presumably, the building was used for county and town business and may have been the office for the Register of Deeds.

When historian and illustrator Benson Lossing visited Hillsborough in 1848, he was told that Cornwallis had used a structure on lot 7 as an office during the British general’s nine-day stay in 1781. Lossing sketched this building while sitting on the piazza of the Union Hotel where he was lodged.

Interestingly, Lossing also noted that, “When James Monroe (afterward President of the United States) visited the Southern army in 1780, as military commissioner for Virginia, he used this building for his office while in Hillsborough.” However, no records indicate that President Monroe ever visited Hillsborough when he was in North Carolina. Instead, in a 1780 letter from Monroe to Thomas Jefferson, who at that time was serving as Governor of Virginia, Monroe clearly stated that he intended to remain in Cross Creek (Fayetteville) and would not be traveling to Hillsborough as planned. Lossing may have heard that Hillsborough merchant James Munro (see ‘Lot 26’) used the building as an office and confused the name with that of the president. Although his home and store were located on lot 26, Munro owned other properties and had a variety of business interests. Accordingly, it is plausible that he might have been using the building on lot 3 as an office in 1780 and 1781. His congenial relationship with Cornwallis makes it more likely that Munro would have allowed the general to use the space as opposed to the next known owner of the property, William Johnston, who was an active Patriot and would have been less inclined to be helpful to Cornwallis.

.jpg)

(L.) Photograph of Benson John Lossing c. 1835

(C.) Lossing’s Pictoral Field Book of the Revolution (1855) Photo courtesy of invaluable.com

(R.) Lossing’s Drawing of Cornwallis’ Office

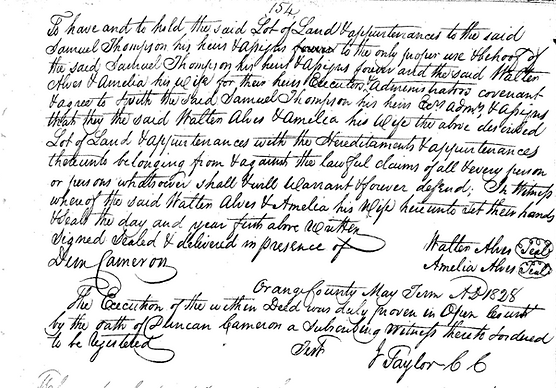

Amelia Johnston and Walter Alves

1785

At time of his death in 1785, Scottish merchant William Johnston owned the property. (See ‘Lot 6’) Johnston bequeathed it to his only daughter, Amelia, and her husband Walter Alves. Afterward, and the property was transferred back and forth with his father James Hogg (Hogg’s children legally changed their surname to their mother’s maiden name in response to teasing). How the Alves and Hogg used the building is unknown but it was most likely for commercial purposes – either for their own or to rent out – since the Alves’ and Hoggs had large private residences nearby.

After moving to Kentucky, Amelia and Walter Alves sold the property to Samuel Thompson in 1806. In 1834, Richard Thompson sold the entire one-acre lot to Thomas Ward. By 1843, the property was owned by Eliza and William Bingham as well as Helen and Andrew Mickle. They sold it that year to John Norwood (1803-1885) who later became a member of the North Carolina General Assembly in 1858 and the North Carolina State Senate in 1872.

Although the lot was not subdivided until 1856 in regard to ownership, the composition of buildings on the property would have needed to change in order to accommodate the size and scope of the various businesses that occupied the space. However, the building that had been used as an office by Churton and Cornwallis was still standing in 1855 when it was noted in an article in the Raleigh Weekly Standard.

.png)

(L.)James Hogg (1729-1804), emigrated from Scotland in 1774. A planter, importer, and land speculator, he became one of Hillsborough’s wealthiest and most prominent men of his day.

(R.) 1803 Deed transferring the property from Walter and Amelia Alves to Samuel Thompson

.png)

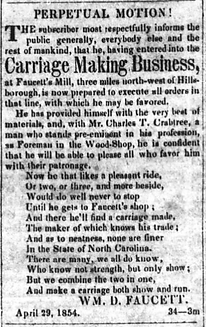

Carriage Making and Repair

c. 1823

In January 1823, David Murden advertised that he had established himself in Hillsborough on Lot 3 and intended to operate a gig and chair making business. A gig was a light, two-wheeled carriage, driven by its owner that was normally drawn by a single horse. It only had room for the driver and a single passenger though usually there was a small seat for the groom behind the body. Some gigs had foldable heads (hoods) for protection from the elements. These had side windows to enable the driver to have some peripheral vision when it was up.

A chair was similar but typically lighter than a gig.

(L) David Murden’s 1823 advertisement in the Hillsborough Recorder.

(R.) An illustration of a gig.

The site remained a carriage shop for many years. In March 1851, Charles F. Crabtree was advertising that he intended to make and repair carriages, barouches, buggies, and sulkies in his shop on Lot 3. Crabtree is recorded as remaining in business until approximately 1877. An 1854 advertisement placed by William Faucett boasted that he was working with Crabtree at Faucett's Mill, three miles north-west of Hillsborough. Consequently, Crabtree may only have worked downtown for three years or he may have worked in two locations.

(L) An 1846 advertisement for Workman & Utley Carriage Making

(C) An 1851 advertisement for carriage repair by Charles Crabtree

(R) William Faucett’s 1854 advertisement for carriage making

Lots 8 and 11 on the west side of Churton Street were also used for carriage making (information on Lot 8 to be added at a later date). On January 1, 1846, Workman & Utley began a carriage making business “near the bridge.” Their partnership was dissolved by the end of the year and John Utley began a new partnership in the trade of carriage making with Culbreth at that same location. In 1849, Utley & Culbreth notified their customers that they had moved “two doors above Nelson’s Store, at the place formerly occupied by Mr. Henry Gorman.” However, this site may have been on North Churton Street. Gorman, who owned property on lots 8 and 11 appears to have started in the carriage making business in 1844. He is presumably the son of Henry Gorman the noted plasterer of Raleigh who worked on the State House as well as locally at Ayr Mount. Gorman the carriage maker also had a shop in Raleigh that was advertised in The Spirit of the Age, a temperance newspaper published by Alexander Gorman (1814-1865), Henry’s presumed brother.

Another carriage maker in town at that time on Lot 8 was William S. Cheek who worked for awhile in partnership with Holloway. William Cheek’s business was later transferred to John A. Cheek.

These c.1900 photos are of the Connor Carriage Company of Amesbury, MA. Although significantly later than any of the operations on Lot 3, the pictures help provide an understanding of the various aspects of carriage making.

(L) Building Frames and attaching wheels.

(C.) In the trimming shop where upholstery and tops are made.

(R.) The paint shop.

Tumbledown House

1839 - c. 1855

On his 1839 map, William Bailey did not record any structure on the lot that was being used for a carriage making business. Instead, he identified only one building and labeled it as being an unoccupied old “tumbledown” house. In 1848, Benson Lossing described this building as being made, “of logs, covered with clap-boards.” He did not comment on the state of repair or disrepair of the structure at that time. Lossing also did not mention any neighboring buildings or businesses. Historians have presumed that this building was the one that William Churton had used as his office and the Alves thereafter.

Lossing also did not mention any neighboring buildings or businesses.

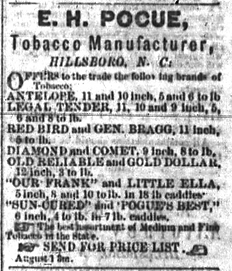

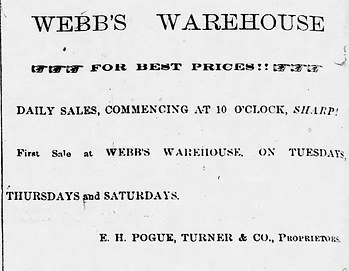

Webb's Warehouse

1872

In 1856, Thomas Webb, who was Clerk and Master of Court of Equity, purchased ¼ of Lot 3, marking the first recorded instance in which the property was subdivided. One year later, Webb offered for sale ¾ of an acre on Lot 3 as part of an equity sale. (In a modern equity sale, a buyer acquires ownership of a business as well as its assets and continues the business under new management). The advertisement for the sale provided no indication as to what, if any, business was being sold in conjunction with the property.

The 9-23-1857 advertisement in the Hillsborough Recorder for the partial sale of Lot 3 by Thomas Webb

At some unrecorded point, this ¾ acre property was purchased by Edmund Strudwick who sold it in 1870 to James Webb Jr., brother of Thomas Webb.

In 1859, James Webb Jr. (1816-1897) partnered with James Young Whitted to form Webb & Whitted, the first commercial tobacco manufacturer in Orange County. It was located on Lot 2 on E. King Street next to the courthouse. When the Civil War broke out, Whitted enlisted in the Confederate army and the firm ceased operations. After the war, Whitted formed a new tobacco business, aptly called J. Y. Whitted & Company. In 1884, Whitted decided to move his processing factory to Durham (then, still in Orange County) where he befriended John Ruffin Green. Whitted is credited as suggesting the name “Bull Durham” to Green for his new blend of tobacco.

When Whitted departed in 1871, Webb (or his son who was also called “James Webb Jr.”) started another tobacco manufacturing factory with William S. Roulhac called Webb & Roulhac. Two years later, this company also moved to Durham. In 1876, Webb left the partnership and the firm's name changed to Roulhac & Company.

In 1871, Webb decided to expand his tobacco business to include operating a warehouse for the storage and sale of leaf tobacco on Lot 3. To accommodate the construction of a warehouse, he presumably removed any existing structures on the property. The warehouse opened for business in January 1872. It was a wooden building measuring 125 feet by 40 feet and was advertised as the "largest and best in North Carolina and the only warehouse in Hillsboro' with Sky-Lights!"

(Above) Interior views of tobacco warehouses during auctions

(Below) Receipt for tobacco held at or purchased from Webb's Warehouse in Hillsboro in 1875 by member of Pope family. The receipt lists buyers by numbers, along with the corresponding weight, price per unit, and total amount for each transaction, written in neat handwriting. The sales sum to an amount, after which the warehouse charges and net proceeds are calculated.

From the collection of the Orange County Historical Museum

Although the warehouse building maintained Webb’s name and he continued to own the property, J. R. Gattis bought the business in 1874. Gattis had been partners with E.H. Pogue in tobacco manufacturing since 1869, and in 1876, Gattis sold the warehouse side of their business to Pogue. In 1878, the partnership dissolved. Pogue moved his new manufacturing firm, called E.H. Pogue & Company, to Durham and sold the warehousing business to C. B. Taylor.

Elbert Harper Pogue (1833-1905) moved to Hillsborough in 1863 with his wife, Emily Holt Steel. When the Civil War ended, Pogue began operating a general store (called a "cash store") on E. King Street. He also manufactured and sold tin ware wholesale and retail at his shop. From 1885-1888, Emily and EH Pogue were the proprietors of the Occoneechee Hotel (known today as the Colonial Inn). After selling the hotel, they moved to Alabama.

(L) An article about the opening of Pogues warehouse from the Hillsborough Recorder,

November 7, 1877.

(C) An advertisement for Webb's Warehouse with E.H. Pogue as the proprietor in partnership with Josiah Turner, June 12, 1886

(R) A reproduction of 1870s E. H. Pogue 'Sitting Bull' tobacco sign

James Webb bought more of Lot 3 in 1880. Webb’s warehouse remained until 1894, when the building was used for general storage purposes. A June 1902 map, hand drawn by Josephine Hassell Parris for a school project lists the lot in the possession of Webb, Clark, and Hinton.

Sanborn maps of Lot 3 depicting its usage as a tobacco warehouse and then storehouse.

(L) 1888. (C) 1894. (R) 1911.

Orange County Public Buildings

c. 1920

By the 1920s, the former warehouse was being used as a garage and as storage for the local school district. At this time, it was also used as the basketball court for Hillsboro High School. Player Joe Rosemond recalled, “They had to move the busses out. ... I just remember thinking, ‘How in the world you could play ball under those conditions? There were grease and mud spots and they had rafters hanging down.” Hillsboro students played there until the first school gymnasium was built across the street from the school in 1929.

In early 1934 a section of it was renovated by the CWA/NCERA for use as town and county offices, including a new office for the mayor of Hillsboro.

Sanborn maps of Lot 3 depicting its usage by the county.

(L) 1924. (R) 1943.

A close-up of the building in 1938

New Orange County Courthouse

1954

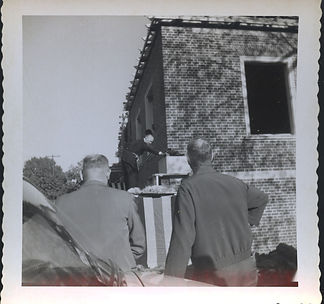

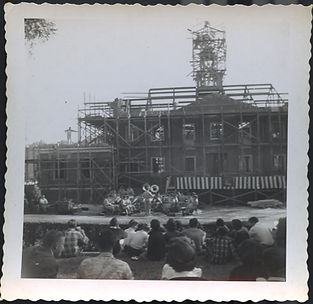

In 1953, the county decided that it needed more office space and hired architect Archie Royal Davis to design a new courthouse in the Colonial Revival-style. The cornerstone was laid on October 7, 1953, in a grand ceremony in which Edwin T. Howard, Grand Master of Masons in North Carolina, conducted the rites with the assistance of Eagle Lodge 19 of Hillsborough. William A. Devlin of the North Carolina Supreme Court delivered the keynote speech that day. It was part of the elaborate weeklong bicentennial celebrations for the founding of the county that included plays, pageants, and parades.

A rendering of the new courthouse by Archie Royal Davis architects

1953 photographs of the cornerstone laying ceremony

From the collection of the Orange County Historical Museum

On year later, county officials moved their offices across the street into the newly completed building. Festive ceremonies were again held to mark the occasion.

As the business of the county grew, subsequent additions were placed on the original building.